Scientists have long struggled to piece together Earth’s ancient air when dinosaurs roamed. Traditional climate proxies – mainly marine fossils and soils – leave massive gaps in our picture of the Mesozoic atmosphere.

Now, a German-led team has cracked open a new data source. By analysing oxygen isotopes in fossilized dinosaur tooth enamel, they have shown the air back then held far more CO₂ than today.

As the University of Göttingen press release notes, “fossilized dinosaur teeth show that the atmosphere during the Mesozoic… contained far more carbon dioxide than it does today”. This breakthrough finally links land animals to the very air they breathed.

Climate Crisis

Today’s CO₂ level – about 420–430 parts per million – is the highest in millions of years. That sharp rise has scientists urgently asking how Earth behaved under similar extremes.

Understanding the dinosaur-age greenhouse world helps test climate models for our future.

During the 165-million-year Mesozoic Era, global temperatures were far warmer, seas were much higher, and forests were lush.

By comparison, “Earth’s atmosphere currently has around 430 parts per million CO₂”. If levels approach those dinosaur-era values again, ecosystems could shift in ways we must better predict.

Fossil Limitations

Until now, paleoclimate reconstructions relied almost entirely on indirect signals. Scientists used marine microfossils and sediment carbonates as proxies for ancient CO₂ – a method biased toward oceans.

Terrestrial conditions remained elusive. In effect, the dinosaur-era atmosphere was hiding in plain sight on land.

As Phys.org explains, previous work “mainly used soil carbonates and so-called marine proxies” to gauge climate, but these have uncertainty.

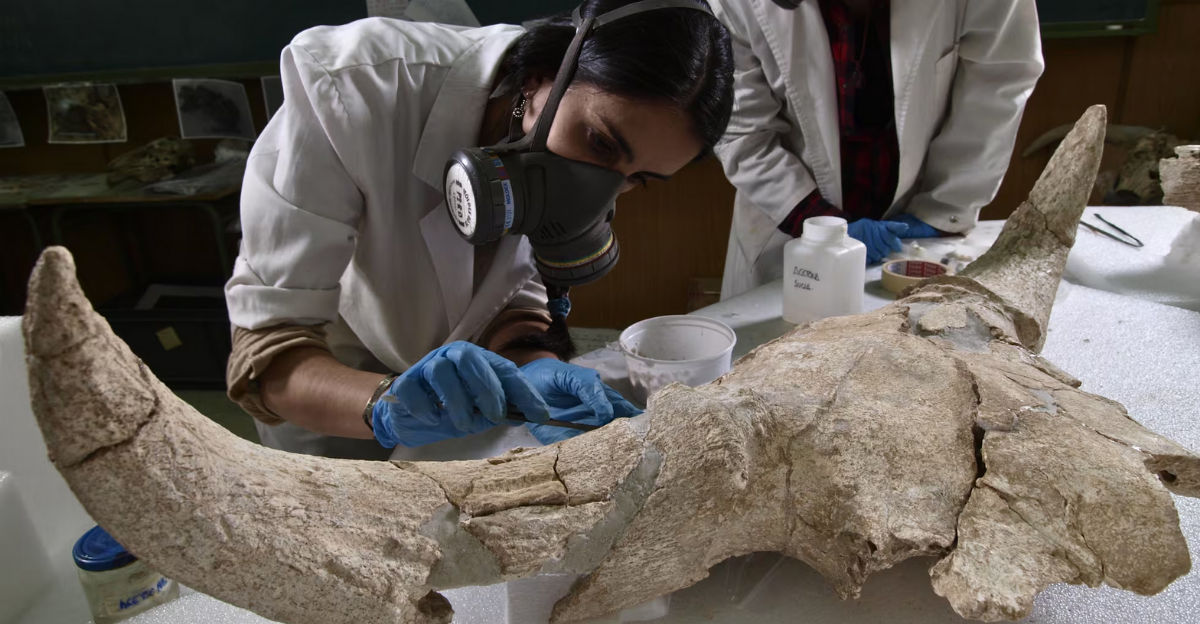

Analyzing dinosaur tooth enamel is the first method to focus directly on air-breathing land vertebrates, filling in those gaps.

Mounting Pressure

Modern climate extremes – droughts, floods and heatwaves – underscore the stakes of this research. International bodies like the IPCC have repeatedly urged more paleoclimate data to refine future projections.

With CO₂ soaring today, scientists need ancient benchmarks.

Dinosaurs lived through some of the highest greenhouse levels known, yet we lacked solid evidence of exactly how high.

Each new fossil finding could revise our story of Earth’s climate sensitivity. In recent years, paleoclimatologists grew desperate for better data linking CO₂ to observed climate change over geologic time.

Breakthrough Discovery

The breakthrough came in August 2025, when Dr. Dingsu Feng’s team published the first direct reconstruction of dinosaur-era air using tooth enamel.

By measuring rare triple-oxygen isotopes (especially oxygen-17) locked in fossil teeth from the Jurassic and Cretaceous, they inferred atmospheric CO₂ concentrations.

Late Jurassic samples implied about 1,200 ppm – roughly four times the pre-industrial level. Lead author Feng hailed the result: “Our method provides us with completely new insights into Earth’s past”.

This new climate “time capsule” finally links land-living dinosaurs to their ancient air.

Regional Impacts

The analysis covered teeth from three continents (North America, Africa and Europe), yet found striking consistency. During the Late Cretaceous, CO₂ levels hovered around 750 ppm – still about three times higher than pre-industrial air.

In other words, dinosaurs on different continents all breathed an atmosphere far richer in greenhouse gas than anything living creatures experience today.

These numbers suggest Earth then was a true runaway greenhouse.

Even modest rises back toward those levels would transform our climate, hinting at how extreme the natural baseline was compared to the modern era.

Human Perspective

The scientists describe the findings in human terms. Paleontologist Thomas Tütken of Mainz says the teeth act like “time capsules” from deep time.

He explains that “even after up to 150 million years, isotopic traces of the Mesozoic atmosphere… are still preserved in fossil tooth enamel”.

In other words, a dinosaur’s bite literally contained a record of the air.

Co-author Eva Griebeler adds that these isotope ratios in enamel can reveal both ancient CO₂ levels and the productivity of the plant-and-animal food web.

After years of lab work, the team finally pulled back the curtain on a long-hidden climate record.

Scientific Competition

The new technique instantly upended paleoclimate research. German universities now lead this field, challenging labs that focused on ocean cores and plankton shells.

The method pressures other teams worldwide to retool: rather than infer air conditions from distant seas, researchers can measure them directly in any terrestrial fossil tooth.

Some climate chemists worry about consistency across labs, but the Göttingen breakthrough sparks a race.

Already, teams in China, the U.S., and elsewhere are racing to apply triple-oxygen analysis to their dinosaur collections.

Macro Trends

These dinosaur-derived data fit the big picture of a long Mesozoic greenhouse. Scientists knew the Jurassic-Cretaceous was warm, but the new precision is unprecedented. For example, Phys.org notes that fossil teeth now confirm “CO₂ in the Mesozoic era… was far higher than they are today”.

In particular, the Late Jurassic atmosphere held about four times as much CO₂ as pre-industrial air.

By contrast, today’s CO₂ (∼430 ppm) is lower by comparison.

These insights give climate modelers the calibration they need for extreme warm climates, making projections for future super-greenhouse scenarios more reliable.

Mini-Nugget Reveal

Perhaps most surprising was a secondary finding in the enamel data. Two particular teeth – one from a Tyrannosaurus and one from a long-necked sauropod – showed dramatic oxygen-isotope spikes.

These “unusual combinations” suggest atmospheric CO₂ surged episodically, likely from massive volcanic eruptions such as India’s Deccan Traps near the end of the Cretaceous.

Even more intriguingly, the team deduced that global plant photosynthesis was roughly double today’s rate.

As co-author Eva Griebeler notes, this “provides important evidence of both marine and terrestrial food webs” built on explosive plant growth.

Internal Tensions

The team’s claims initially met skepticism. Traditionalists questioned whether delicate oxygen signatures could survive in teeth for tens of millions of years. Still, the German scientists persevered.

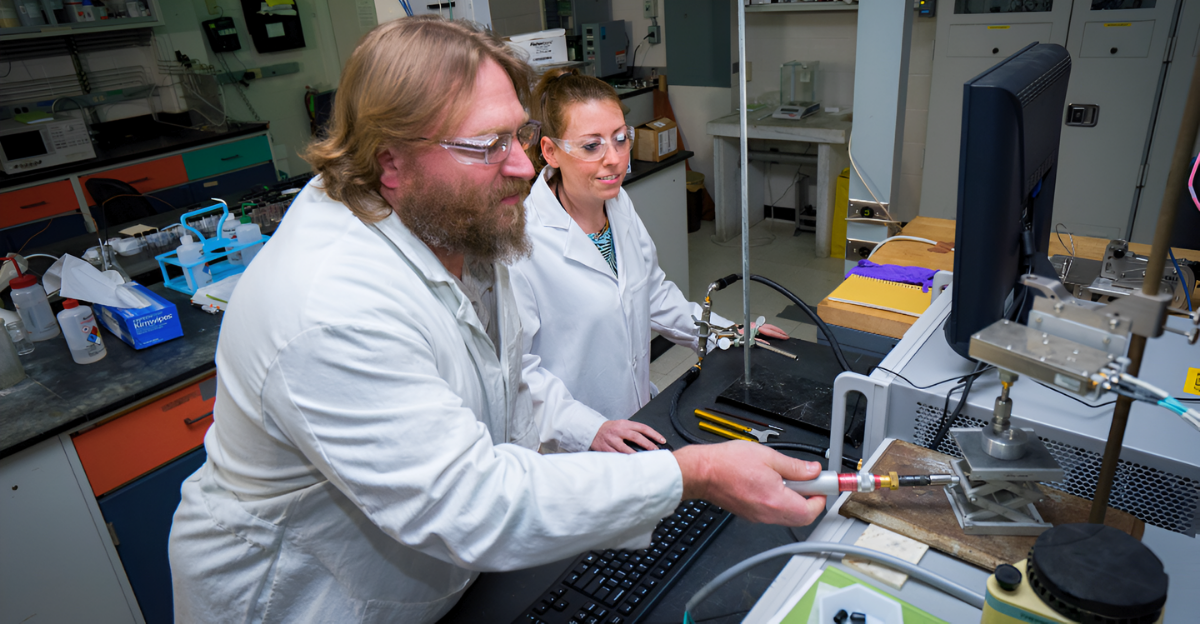

They subjected the samples to rigorous cross-checks and peer review. The eventual PNAS publication showed their lab protocols were sound.

By painstakingly ruling out contamination and reproducing the isotope ratios across multiple laboratories, they won over many doubters.

In the end, even critics admit the technique holds promise, though many urge more independent replication before fully retiring the old marine-proxy approach.

Leadership Shift

The project’s success also marked a new chapter for its young leader. Dr. Dingsu Feng, who did her doctorate in Göttingen’s geochemistry department, emerged at the helm of what some senior colleagues once saw as an overly ambitious “fishing expedition.”

Backed by a team spanning Göttingen, Mainz and Bochum, she shepherded a diverse group of geochemists, paleontologists and climate experts.

Professor Andreas Pack of Göttingen provided crucial isotope-analysis expertise behind the scenes.

Together, the collaboration blended traditional paleontology with cutting-edge isotope geochemistry – a novel model for future climate investigations.

Strategic Validation

To validate their atmospheric CO₂ estimates, the researchers left no stone unturned. They analyzed teeth from multiple dinosaur species (herbivores and predators) and from different eras.

In the lab, high-precision mass spectrometers measured tiny ¹⁷O anomalies to parts-per-million accuracy.

They then cross-checked the isotope-derived CO₂ reconstructions against independent geological markers – for example, known volcanic timelines and temperature proxies.

The consistency held: every independent line of evidence pointed to similarly high greenhouse gas levels, boosting confidence in this vertebrate-based proxy.

Expert Assessment

Independent experts have hailed the method as innovative, though cautioning that “more work lies ahead,” as one climate scientist put it.

Many agree the triple-oxygen approach is a game-changer, but want data from other fossil beds worldwide before overhauling textbooks.

Paleoclimatologists emphasize the need for analyses of tooth enamel from, say, dinosaur-bearing rocks in South America or China.

The PNAS review process itself was unusually rigorous, with reviewers poring over the statistical treatment of the isotope data.

The result passed muster, but consensus will only solidify as the technique is widely tested.

Future Implications

This work raises profound questions about our planet’s resilience. If Earth once flourished with 3–4 times today’s CO₂, what does that say about modern ecosystems facing a rapid rise toward those levels? The data show our climate can exist in a state far more extreme – but at a cost.

Ancient forests stretched from pole to pole in high-CO₂ warmth.

Today’s species, evolved for cooler ice-age climates, might not fare the same way.

Ecologists now wonder which extinct dynamics will re-emerge. Clearly, the dinosaur-age greenhouse was stable over millions of years, but its ecology was unlike anything we see now.

Policy Ramifications

Policymakers now have hard paleodata for “worst-case” scenarios. Long-term climate targets may need re-evaluation in light of this evidence. For example, understanding that CO₂ can naturally reach dinosaur-era levels suggests carbon cycle feedbacks and tipping points differ from prior assumptions.

Climate advisors could use these benchmarks to stress the importance of keeping emissions far below those prehistoric peaks.

International negotiations might be influenced by knowing exactly what happened when CO₂ was triple today’s levels, particularly if volcanic events can still trigger similar spikes. The study thus adds urgency to carbon-reduction timelines.

Global Consequences

Around the world, dinosaur-rich nations are waking up to the opportunity. Institutions in Argentina, China, the U.S., and elsewhere are eyeing their fossil collections for climate clues.

The goal is a global network of Mesozoic CO₂ measurements. By applying the tooth-enamel method to local specimens, countries can take part in this revolution.

Future studies could reveal regional variations – perhaps different vegetation patterns or eruption histories in Gondwana vs Laurasia.

In effect, the methodology democratizes paleoclimate data. Whoever has dinosaurs on display now holds records of ancient air to unlock.

Environmental Context

For most modern species, the dinosaur climate would be deadly. Air with >1,000 ppm CO₂ and temperatures many degrees higher would melt ice caps and choke temperate zones. Habitats that humans depend on today simply did not exist then.

Conservation laws written for current climate baselines may need revision if we learn how ecosystems coped back then.

Importantly, the findings highlight how fast today’s change is compared to natural shifts: dinosaurs’ world changed over millions of years, whereas our atmosphere is leaping toward those levels in decades.

This gap in tempo will be critical for biodiversity.

Cultural Shift

This discovery is already altering our mental picture of dinosaur times. Gone is the outdated notion of a mild Jurassic Eden. Classrooms and museum halls will soon depict dinosaurs in blazing heat amid vast fern jungles and frequent volcanic skies.

“Jurassic World” imagery is giving way to a more scientific narrative: dinosaurs endured a hothouse planet.

Educators are updating curricula, and natural history museums plan to revise their displays.

We will tell students that Tyrannosaurus walked in an atmosphere no human could breathe – a fact underpinned by data from the dinosaurs’ own teeth.

Broader Reflection

Ultimately, this advance is a triumph of creativity. It shows how a clever twist – analyzing a lost isotope in a new medium – can unlock Earth’s secrets.

Terrestrial fossils have become climate time capsules, revolutionizing our toolkit.

In Dr. Feng’s words, dinosaurs are nearly “climate experts”: their teeth recorded the air over 150 million years, and at last we can read that record.

As we confront unprecedented climate change, these ancient archives offer both warning and hope. They remind us that even record-breaking conditions have occurred before, guiding how life adapts or perishes under a greenhouse sky.